In the previous post we looked at the functions TRY_CAST, TRY_CONVERT, and TRY_PARSE and how they compared. I wrapped up and said that my preference for new developments would be to use TRY_PARSE due to the tighter control which it provides us.

As with everything in SQL Server however, there is no ‘best’ approach, it depends. I therefore wanted a separate post to look into the specifics with TRY_PARSE and areas where it may work more or less effectively.

Culture awareness

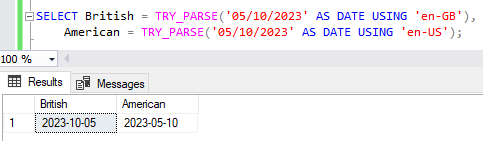

One of the benefits to TRY_PARSE is the ability to specify the culture we’re using to parse the data. This helps us to correctly parse elements such as dates which can differ in format between regions.

Being in the UK I’ve seen inconsistent configuration across environments or applications (typically American versus British) due to default installation configuration being used. This can lead to issues where one system is exporting data in one format and another is attempting to import into another.

Below demonstrates how TRY_PARSE can resolve this issue by specifying the optional culture argument to define how the formatting is handled:

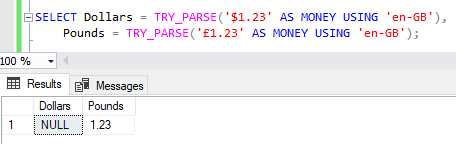

The same benefits are also seen with currencies. If we attempt to parse a value using a British culture then a preceding dollar symbol would fail conversion and return NULL however a preceding pound symbol would be acceptable:

Erroneous data

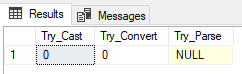

Using regular CAST or CONVERT functions for data conversion, our statements will fail when any of the values fails conversion. By using the TRY_* functions we can alleviate these issues. For example the statement below will return a NULL value:

SELECT TRY_PARSE('ONE' AS INT);

That’s the same for all of the TRY_* functions however, so what is different with TRY_PARSE?

Well in this case it’s the blank values which make the difference. Empty strings aren’t uncommon when ingesting data and how they’re handled may be important for us. By using TRY_PARSE any empty strings would be converted to a NULL value:

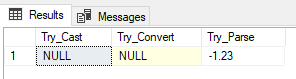

SELECT TRY_CAST('' AS INT) AS [Try_Cast],

TRY_CONVERT(INT, '') AS [Try_Convert],

TRY_PARSE('' AS INT) AS [Try_Parse];

If identifying the difference between a zero and blank value is key, this feature may be helpful.

The CLR in the room

We had the TRY_PARSE function added at the same time as TRY_CAST and TRY_PARSE. They all convert data for us, and the results from all of them are very similar. So are our execution plans:

We have the three functions and the executions plans for converting the same data using each function. Each query has equal cost relative to the batch and operators also have the same weighting.

This isn’t the full story. The documentation tells us more:

TRY_PARSE relies on the presence of .the .NET Framework Common Language Runtime (CLR).

Although not shown on our execution plan, we’ll be calling out to the .NET CLR to execute the function. This isn’t the case for TRY_CAST and TRY_CONVERT.

Using the CLR isn’t itself a benefit or drawback of the function, it’s a double edged sword. This has both helpful and not-so-helpful results which we’ll look at below.

Format compatibility

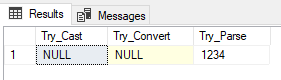

The implementation of the function with the CLR makes the TRY_PARSE function more flexible when it comes to handling different number formats.

In the documentation it details which SQL types map to which .NET types, and more importantly which style is used for conversion. Based on that we can check the NumberStyles enumeration in the .NET documentation. Towards the end of the document we can see which flags are applicable to each of the number styles to see what the parsing will support.

For example we can see that the SQL INT uses the Number style which allows thousand separators to be handled:

SELECT TRY_CAST('1,234' AS INT) AS [Try_Cast],

TRY_CONVERT(INT, '1,234') AS [Try_Convert],

TRY_PARSE('1,234' AS INT) AS [Try_Parse];

In another example the SQL MONEY type uses the Currency style which supports parentheses to indicate negative values:

SELECT TRY_CAST('(1.23)' AS MONEY) AS [Try_Cast],

TRY_CONVERT(MONEY, '(1.23)') AS [Try_Convert],

TRY_PARSE('(1.23)' AS MONEY) AS [Try_Parse];

Being able to support these formats out of the box can make this function more effective at dealing with a variety of data which would otherwise need to be handled differently.

Performance

Now we get to the downside of the function.

There’s no getting away from the fact this function uses the CLR. That’s extra overhead we have with this method. It brings us the parsing benefits above, but at a cost.

Let’s build 100k records of test data to demonstrate:

CREATE TABLE #TestData (TestDate VARCHAR(50));

CREATE TABLE #DateStyles (ID INT IDENTITY(0, 1) PRIMARY KEY, Style INT);

/* Choose the styles we want to use (day first for GB) */

INSERT INTO #DateStyles (Style)

VALUES (0), (3), (103), (4), (104), (5), (105), (6), (106)

/* Insert 100k records in 2023 using styles above */

WITH Prep AS (

SELECT

TOP (100000)

DaysToAdd = CAST(RAND(CHECKSUM(NEWID())) * 365 AS INT),

StyleID = CAST(RAND(CHECKSUM(NEWID())) * 9 AS INT) /* 9 styles above */

FROM sys.objects a

CROSS JOIN sys.objects b

CROSS JOIN sys.objects c

)

INSERT INTO #TestData (TestDate)

SELECT CONVERT(VARCHAR, DATEADD(DAY, p.DaysToAdd, '2023-01-01'), s.Style)

FROM Prep p

LEFT JOIN #DateStyles s ON p.StyleID = s.ID;

Now if we query that for say 100 records, all of the data will return instantly:

SELECT TOP (100) *, TRY_CAST(TestDate AS DATE) FROM #TestData;

SELECT TOP (100) *, TRY_CONVERT(DATE, TestDate) FROM #TestData;

SELECT TOP (100) *, TRY_PARSE(TestDate AS DATE USING 'en-GB') FROM #TestData;

That’s fine for small data volumes. If we increase the volume to 1,000 records we may see a slight delay, but still minimal. However, when we retrieve all of them we can see the impact at scale. Below are the statistics for all 100k records on my rig:

| Function | CPU time | Elapsed time |

|---|---|---|

| TRY_CAST | 62ms | 665ms |

| TRY_CONVERT | 31ms | 795ms |

| TRY_PARSE | 8063ms | 9451ms |

The execution plans looks the same as we saw previously but they’re not telling the full story. It’s worth noting that the elapsed time for the TRY_CAST and TRY_CONVERT functions is primarily from returning the data back to Management Studio.

If you’re dealing with low volume, say checking individual values being passed into a procedure, or small-batch data processing then you likely won’t notice this impact at that scale.

Once your workload grows to large batches you may feel the sting of this function. Your execution plans may not help you identify the reason for this either as we saw them looking very similar above.

Wrap up

As I said last time, I like the TRY_PARSE function due to the behavior we have when dealing with a variety of values and formats. The flexibility and control it provides us is superior to the TRY_CAST and TRY_CONVERT alternatives. That is why this is my preference to use for new code as it provides a more robust solution.

With that said, we’ve seen how this function relying on the CLR limits its scalability. If we know ahead of time that we’ll be dealing with larger volumes of data – or that we need to scale to be able to support that – then it may be better to look into alternatives such as the other TRY_* functions.

Another element to consider is whether the flexibility is required for your usage. If you’re dealing with a 3rd party where you have little to no control over the format then flexibility could be more beneficial. If you have well defined and structured data being exchanged then some of the benefits may be moot points.

One reply on “A Focus on TRY_PARSE Functionality”

[…] Andy Brownsword takes a closer look at TRY_PARSE(): […]