In the previous post I explained Join Operators in SQL Server. Whilst compiling that I dug a little deeper and came across a few interesting points I thought were worth sharing.

Let’s look at behaviour of the operators which may occur under specific conditions. Hopefully you find them as interesting as I did:

Optimised nested loop joins

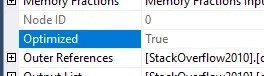

Nested Loop operators have an internal optimisation which isn’t clear unless you pay attention to them in the plan. They have a singular property which indicates if the join has been optimised:

But what does this hidden optimisation involve?

An optimised join will shuffle the input records in a best-effort reordering. This isn’t a full Sort so won’t leave the records ordered, however it avoids the need for a full Sort operator. This happens if the engine thinks a sorted input may be beneficial for lookup efficiency, but not so much that it needs one.

The optimisation is at an operator level, so it won’t necessarily be the case that all Nested Loops in a plan will be optimised. In the example below the first join in the plan (orange) is unoptimised whereas the engine chose to have the second (green) one be optimised.

I spotted a post by Kendra where she noted that performance can be slow without this optimisation, and whilst there’s a hint to disable the optimisation, there isn’t one to force it. She also references a fantastic in-depth post from Craig Freedman about the optimisation.

If you spot these in your query plan – good news. If you’re seeing unoptimised joins and your data has potential for bad estimates due to predicates or data skew, consider splitting the query, or remove the need for additional lookups with a covering index.

Many-to-many merge joins

Merge Joins do their duties by walking through two sets of ordered input and comparing the records of both inputs to return required records.

This approach breaks down if there are duplicates present on both sides – a many-to-many scenario. It has to deal with these joins differently, and once again it’s not obvious at first sight.

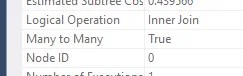

It’s the same story of taking a look at the operator properties to see that a many-to-many merge was used:

How does a many-to-many join differ?

Let’s say we have 2 duplicate records on one input, and 3 duplicates on the other. A Merge Join only wants to move forwards through the sorted records. To produce all permutations, duplicates from one of the inputs are placed into a worktable. The worktable can then replay those values as many times as needed for duplicates on the other input.

This worktable allows the join to provide all permutations and still allows the Merge Join to proceed through the ordered records without the need for any type of rewind.

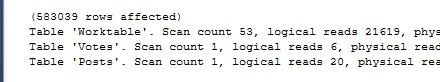

We can see the heavy action on the worktable in the statistics:

Whilst the Merge Join can be an effective choice for the optimiser with ordered inputs, this Many-to-Many variety has additional overhead due to the replaying records from the worktable, requiring plenty of I/O. If we’re not observant and notice this it can really cripple performance.

Here’s a post from Erik where he also notes the performance impact, and that the engine can even inject aggregates into the plan to make one of the inputs unique to avoid these Many-to-Many operations.

If you see signs of these Merge Joins performing a Many-to-Many join, or where aggregates are getting added to the plan, you can review tables to ensure uniqueness is defined through an index or constraint. If the join is intentionally many-to-many you could consider an alternative join operator, although I’d advise against using hints to force that.

Recursive hash joins

Hash Match joins are the heavyweights that can deal with large volumes of unsorted data at the expense of resources due to their hashing. But what if the volumes of data are just too large for memory?

The Hash Match Join has a solution for that – a Recursive Hash Join.

If there’s insufficient memory to hash all of the build input (the smaller set, used to create buckets), both inputs are split into multiple partitions. Partitions are based on a hash so partitions from each input are aligned and can be processed in pairs. If partitions are still too large for available memory, partitioning can occur again (and again), hence being recursive.

There is a limit to the amount of recursion which can take place, after which the operator ‘bails out’ and matching falls back to a loop-type comparison. This limit is 5 recursions, however Erik has noted it may be lower with batch mode.

By breaking the volume down in this way, the hash match can complete within the memory available. This strategy has two main performance impacts however:

- Extra work partitioning inputs and the hashing involved

- Hitting the recursion limit falls back to a suboptimal algorithm

If you see recursive hash joins (these raise Hash Warning events) it can be helpful to update statistics on the columns being joined to improve incorrect estimates. Alternatively, consider if the volume of data is required in a single operation, or there’s an alternative approach such as batching over multiple executions.

Wrap up

There’s plenty of layers when you dig into SQL Server. From writing queries to checking query plans, and from understanding operators to digging into the more obscure ways they can operate.

These scenarios aren’t in your face in a query plan so they can be elusive to spot. They aren’t elements I’ve had issues with previously, so the advice provided around handling these is based on helpful pointers from the SQL Server documentation or blogs from across the community.

I found them particularly interesting and eye opening to a level I hadn’t considered before. I’ve certainly been on the lookout for these nuances when reviewing my query plans recently. Keep an eye on the properties of those operators 🔍

2 replies on “Discovering More About Join Operator Internals”

[…] Andy Brownsword takes a closer look at the big three join operators in SQL Server: […]

[…] are always interesting to dig into – join operators are common but the internals are […]