When eliminating NULL values with SQL Server queries we typically reach for ISNULL or COALESCE to do the job. Generally speaking they’ll provide equivalent results, but they work in different ways. If you’re dealing with logic more complex than ISNULL(ColA, ColB) – for example using a function or subquery as part of the expression – then you might be in for a surprise.

The content of expressions when evaluating NULL values can have big implications on query performance. In this post we’ll look at how the functions work and the implications they can have when evaluating NULL values.

For these examples I’ll be using the 10gb StackOverflow database with this index to keep the query plans tight:

CREATE INDEX PostTypeID_ParentID_Inc

ON dbo.Posts (PostTypeID, ParentID)

INCLUDE (AnswerCount);

ISNULL

The ISNULL function is the go-to for eliminating NULL values. ISNULL(ColA, ColB) will return the value in ColA for non-NULL values, otherwise return the value in ColB. This SQL Server specific implementation appears simple on the surface. The way it evaluates those arguments might be surprising.

The ISNULL function may evaluate both expressions when executing, even when the second expression won’t be needed. A simple example:

SELECT ISNULL(is_nullable, 1 / 0)

FROM sys.columns;

Divide by zero error encountered.

The is_nullable column is (ironically) nullable, even though the column doesn’t contain NULL values. Because the first expression can be NULL, the optimiser can evaluate the replacement value during execution. This is why our 1 / 0 is throwing up an error, even when it won’t ever be returned for this example.

This can make the ISNULL an expensive operation where the first parameter is usually populated, and we have a function or subquery as the fallback value. This can cause the optimiser to introduce additional work which isn’t needed.

Here’s an example from the StackOverflow database:

SELECT p.Id,

ISNULL(p.AnswerCount,

(SELECT COUNT(1)

FROM dbo.Posts x

WHERE x.PostTypeId = 2 /* Answer */

AND x.ParentID = p.Id))

FROM dbo.Posts p

WHERE PostTypeId = 1; /* Question */

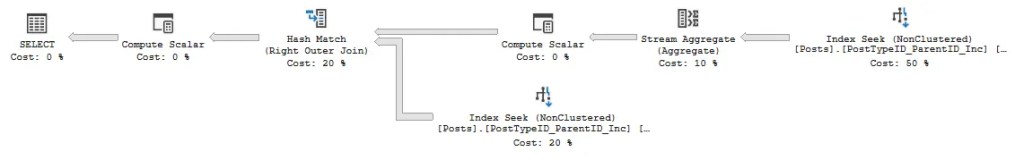

The AnswerCount column is NULLable, however it doesn’t contain any NULL values. Without the ISNULL the logical reads were 2852, however with the ISNULL and the subquery it increases to 9894 (250% increase).

Another aggravation with ISNULL is that it’s restricted to 2 expressions, so if we wanted a further fallback we have to stack them, for example:

SELECT p.Id,

ISNULL(ISNULL(

p.AnswerCount,

(SELECT COUNT(1)

FROM dbo.Posts x

WHERE x.PostTypeId = 2 /* Answer */

AND x.ParentID = p.Id)),

0)

FROM dbo.Posts p

WHERE PostTypeId = 1; /* Question */

The plan is identical as we’re using a static fallback value. Notice that there’s only one path with the aggregate in the plan still (‘of course there is, why wouldn’t there be?’ – I can hear you, bear with me!). It’s no more or less optimal than the previous example. Your scripts can get very busy with brackets if you end up stacking too many ISNULL functions though.

What we’d ideally like is a single function which caters for multiple expressions and avoids evaluating replacement values unless the prior value returns NULL. That’s where we come onto…

COALESCE

The COALESCE function can be used somewhat interchangeably with ISNULL and feels very similar. This function comes from the ANSI standard so may be more familiar to developers from other database platforms. The syntax is the same as ISNULL too, but with the option for additional parameters if you have multiple fallback values.

Behind the scenes, the COALESCE function is actually a facade for a CASE expression. When we use COALESCE(ColA, ColB, ColC) the optimiser evaluates it as:

CASE

WHEN ColA IS NOT NULL THEN ColA

WHEN ColB IS NOT NULL THEN ColB

ELSE ColC

END

This brings benefits and drawbacks.

A key benefit of the underlying CASE statement is that it can ‘short-circuit’ expression evaluation. Where we saw ISNULL potentially evaluating all conditions, a COALESCE has the ability to evaluate only what it needs until a value is returned, which is known as short-circuiting. If ColA isn’t NULL then ColB will never be checked. This avoids the drawback we saw with ISNULL.

Let’s run the same example as above but with COALESCE:

SELECT p.Id,

COALESCE(p.AnswerCount,

(SELECT COUNT(1)

FROM dbo.Posts x

WHERE x.PostTypeId = 2 /* Answer */

AND x.ParentID = p.Id))

FROM dbo.Posts p

WHERE PostTypeId = 1; /* Question */

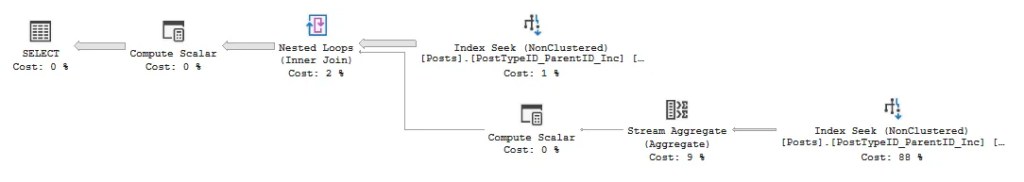

The query plan looks similar, but with short-circuiting in effect from the CASE statement, the lower path in the plan isn’t needed, and the reads drop back down to 2852.

So should we stick to COALESCE and avoid ISNULL? – Not quite, there’s a catch…

The downside of the CASE implementation is that when using expressions, they can be evaluated twice. Notice in the CASE syntax above that ColA and ColB are referenced twice? If they return a non-NULL value, they’ll be evaluated again.

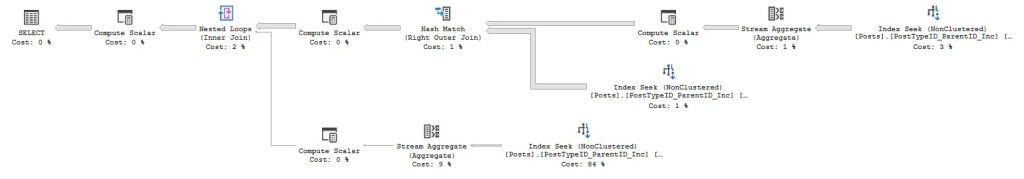

By adding a 3rd condition to the COALESCE, we can see the aggregate from the following query appearing twice in the query plan:

SELECT p.Id,

COALESCE(

p.AnswerCount,

(SELECT COUNT(1)

FROM dbo.Posts x

WHERE x.PostTypeId = 2 /* Answer */

AND x.ParentID = p.Id),

0)

FROM dbo.Posts p

WHERE PostTypeId = 1; /* Question */

In our example it’s not dangerous as we know that AnswerCount will always be populated, so this doesn’t impact the reads. However, if we remove the AnswerCount and need to evaluate the subquery (twice):

SELECT p.Id,

COALESCE(

/* Removed AnswerCount */

(SELECT COUNT(1)

FROM dbo.Posts x

WHERE x.PostTypeId = 2 /* Answer */

AND x.ParentID = p.Id),

0)

FROM dbo.Posts p

WHERE PostTypeId = 1; /* Question */

Now we’re hitting 3,155,493 reads. Yikes.

If you have expensive expressions, subqueries, or functions within the COALESCE which are likely to be triggered, the cost can increase quickly. The same double-evaluation behavior for an expression doesn’t happen with the ISNULL function.

Remember this example from earlier?

SELECT p.Id,

ISNULL(ISNULL(

p.AnswerCount,

(SELECT COUNT(1)

FROM dbo.Posts x

WHERE x.PostTypeId = 2 /* Answer */

AND x.ParentID = p.Id)),

0)

FROM dbo.Posts p

WHERE PostTypeId = 1; /* Question */

The ISNULL function only evaluates each expression once, and it uses the value which is returned without the need for a second evaluation like we see with COALESCE.

Just to compound the pain, by having the expression evaluated twice you can end up with different results returned from each execution.

So both ISNULL and COALESCE have their challenges. What are our options?

Avoiding over-thinking

The aim here is to avoid excessive processing. In the examples above we saw how expression evaluation can be unintuitive and in some cases expensive. How to solve this will vary between different sets of data, but we’ll look at a couple of options.

A simple and effective approach is to split the function into multiple parts and persist values in a temporary table. This ensures expressions are only evaluated once, and only where missing values are still present. Based on the examples above, it may look like this:

CREATE TABLE #Posts (

PostID INT PRIMARY KEY,

AnswerCount INT

);

INSERT INTO #Posts

SELECT Id, AnswerCount

FROM dbo.Posts

WHERE PostTypeId = 1; /* Question */

UPDATE p

SET p.AnswerCount = (

SELECT COUNT(1)

FROM dbo.Posts x

WHERE x.PostTypeId = 2 /* Answer */

AND x.ParentID = p.PostID)

FROM #Posts p

WHERE p.AnswerCount IS NULL;

UPDATE p

SET p.AnswerCount = 0 /* Default */

FROM #Posts p

WHERE p.AnswerCount IS NULL;

Another option is to build a native CASE statement with selective clauses in order of increasing complexity. The goal here is to get the benefit of short-circuiting and drop out of the CASE as soon as it’s feasible to find a result. Logic for expensive expressions should be as late as possible to try and avoid their evaluation. Short circuit evaluation isn’t strictly guaranteed, so this approach will reduce the risk but not eliminate entirely.

UPDATE: Whilst we’re looking at solutions, check out Erik Darling and his comment below where he’s added two more examples that reshape the plans while maintaining the ISNULL and COALESCE syntax.

It should also be noted that a solid schema design can avoid complications with either of these. Ensuring that column values are populated and fields marked as NOT NULL, we negate the behaviour above as the engine will optimise and simplify the plan accordingly.

Wrap up

In this post we’ve looked at expression evaluation with ISNULL and COALESCE functions. Whilst both work well for simple column references, introducing complex expressions, subqueries, or functions can become expensive if evaluation isn’t considered.

The ISNULL function can add overhead by evaluating fallback expressions which aren’t needed, and COALESCE can evaluate expressions multiple times due to the underlying CASE statement.

With a solid understanding of both your data and these functions, you can make decisions on which function is most appropriate. If the cost for evaluation is too high, we’ve looked at alternatives which may be more effective. These will be more verbose, however they’ll provide greater control over expression evaluation and reduce the risk of surprises.

When eliminating NULL values using expressions, the choice between ISNULL vs. COALESCE changes from preference to performance.

6 replies on “Understanding Expression Evaluation with ISNULL and COALESCE”

[…] Andy Brownsword takes a peek: […]

You can get an equivalent plan with ISNULL by adding a TOP (1) to the subquery:

SELECT

p.Id,

AnswerCount =

ISNULL

(

p.AnswerCount,

(

SELECT TOP (1) /*New*/

COUNT_BIG(*)

FROM dbo.Posts AS p2

WHERE p2.PostTypeId = 2 /* Answer */

AND p2.ParentId = p.Id

)

)

INTO #first

FROM dbo.Posts AS p

WHERE p.PostTypeId = 1; /* Question */

You can also get rid of the duplicative branches by using OUTER APPLY with COALESCE:

SELECT

p.Id,

AnswerCount =

COALESCE

(

p.AnswerCount,

oa.AnswerCount,

0

)

INTO #second

FROM dbo.Posts AS p

OUTER APPLY

(

SELECT

AnswerCount = COUNT_BIG(*)

FROM dbo.Posts AS p2

WHERE p2.PostTypeId = 2 /* Answer */

AND p2.ParentId = p.Id

) AS oa

WHERE p.PostTypeId = 1; /* Question */

As a side note, there is a missing comma in your second COALESCE query after p.Id.

Thanks Erik, really appreciate your experience and insights.

It’s great to see how such small changes alter the plan dramatically.

The OUTER APPLY example removes the double evaluation and cleans up the plan nicely. When I’ve tested this, I see the subquery execute for each record so some short-circuiting benefit is reduced, but if you’re expecting most cases to hit that expression it would be a solid optimisation.

Also, the comma has been reinstated after going AWOL 🫡

Yes, always quite amusing what differences small changes can make. Quite a piece of software.

I suppose if you wanted to tune for a specific scenario, you could add an appropriate filter to the OUTER APPLY to remove rows where AnswerCount isn’t all NULLy, or just a zero in this case.

[…] week we looked at how expressions are evaluated with the ISNULL and COALESCE functions. Whilst we’re in the area it’s worth […]

[…] with a vast audience. On top of that I’m honoured to have had Erik Darling jump into the comments with examples recently, and being featured in Brent Ozar‘s Weekly Links on a few occasions has been a particular […]